COMPLEMENTARY WORK FORCE

Virginia's Department of Game & Inland Fisheries is—as is probably true of nearly all such agencies—underfunded for the work it does. In my region, two Conservation Police Officers (CPOs) have responsibility for a vast area, covering at least two and possibly three counties. In addition, this part of the state is very rural and has a lot of hunting and fishing activity, so there are other non-LEO members of the agency who have lots to do to maintain the excellent outdoors opportunities those of us fortunate enough to live in the New River Valley enjoy.

Virginia's Department of Game & Inland Fisheries is—as is probably true of nearly all such agencies—underfunded for the work it does. In my region, two Conservation Police Officers (CPOs) have responsibility for a vast area, covering at least two and possibly three counties. In addition, this part of the state is very rural and has a lot of hunting and fishing activity, so there are other non-LEO members of the agency who have lots to do to maintain the excellent outdoors opportunities those of us fortunate enough to live in the New River Valley enjoy.

One way they do this is to utilize volunteer labor. I have since 1996 been a Hunter Education Instructor, which is one aspect of their volunteer program, but they also maintain a corps of people who do other things besides educating new hunters. This is the "Complementary Work Force" (CWF) program. The CWF has the chance to do many things that need to be done, some of which are summarized here on the DGIF web site.

I just retired from my 28 years at Virginia Tech's veterinary school. I've been a hunter and fisherman for 50+ years, as well as a professional educator. I have a good many skills that I thought they could use, based on the listings, so I applied to join the CWF last month. It looked like a good "fit" for me, and as I am not yet so decrepit that I can't do anything beyond staring at a wall and drooling, I wanted to give it a try.

Yesterday, December 22, I had my first assignment.

I was part of an operation stocking 800 pounds of rainbow trout into Big Stoney Creek in Giles County. It was fun, not too strenuous, and (I hope) it furthered DGIF's goals.

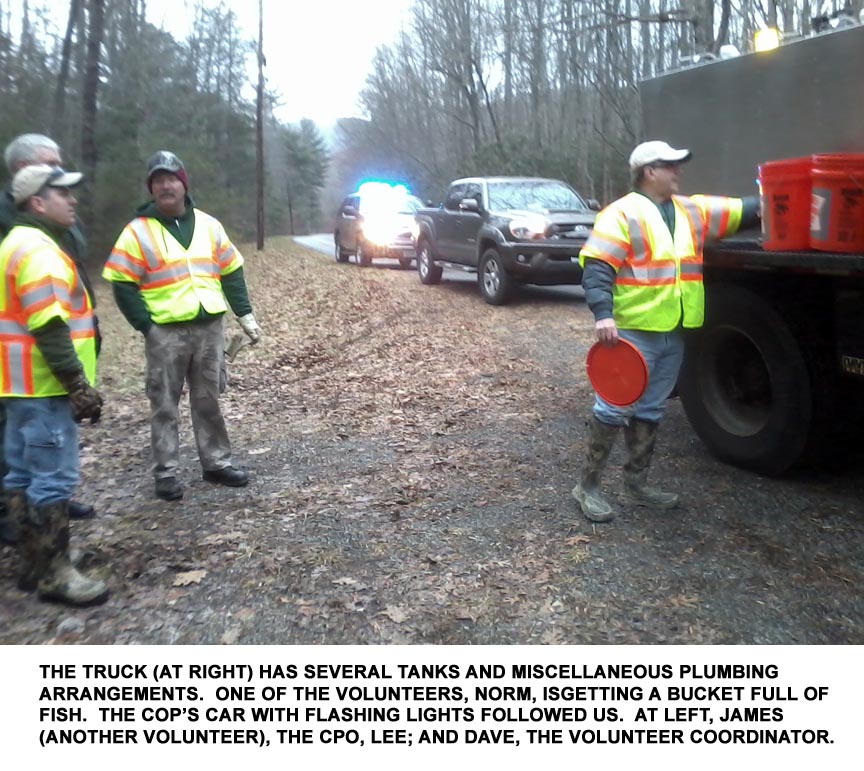

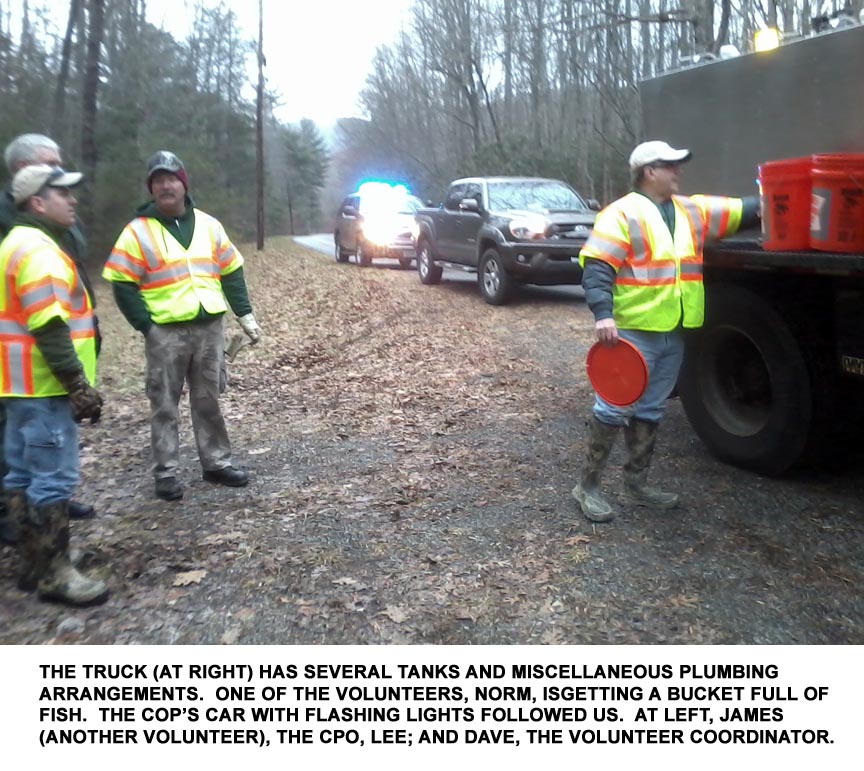

I managed to drag myself out of bed to meet the CPO, volunteer coordinator, and two other volunteers at the Hardee's in Pearisburg (25 miles from my home). We all then carpooled to a spot deep in the Jefferson National Forest, where we met the hatchery truck. The other two volunteers were a youngish professor from UVA's Wise satellite campus, and a retiree who said he used to own a Chick-Fil-A restaurant. We'll probably encounter each other again in the future.

The truck is a big Ford diesel flatbed with stainless steel fish tanks on top. There's a cylinder full of oxygen on the back, various hoses, and a couple of nets for scooping fish out of the tanks. The driver was a genial young man named Zack, a DGIF hatchery employee, who has done this many times. My fellow volunteers all knew the drill and the spots where we'd throw the fish in the creek, but I was a newbie. The weather was damp, chilly, and occasionally rainy. We all wore muck boots, AND a fluorescent yellow and orange vest for visibility. As we did the stocking the CPO followed us in his car with the light flashing to prevent us from being run over.

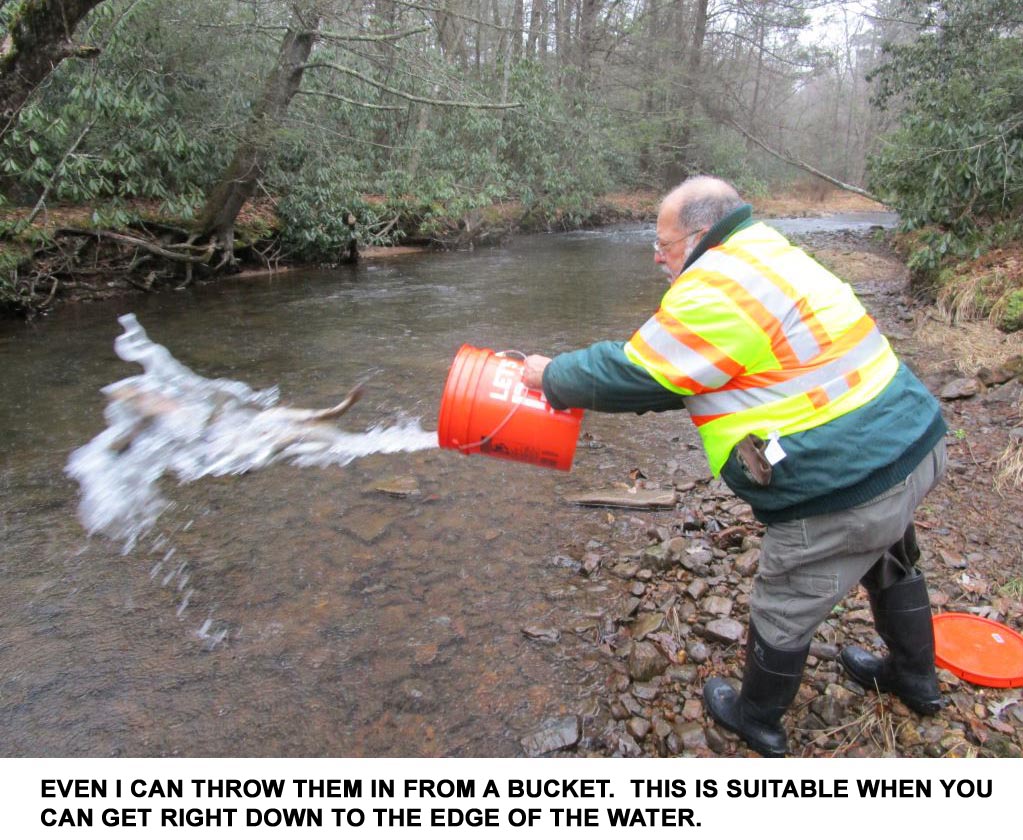

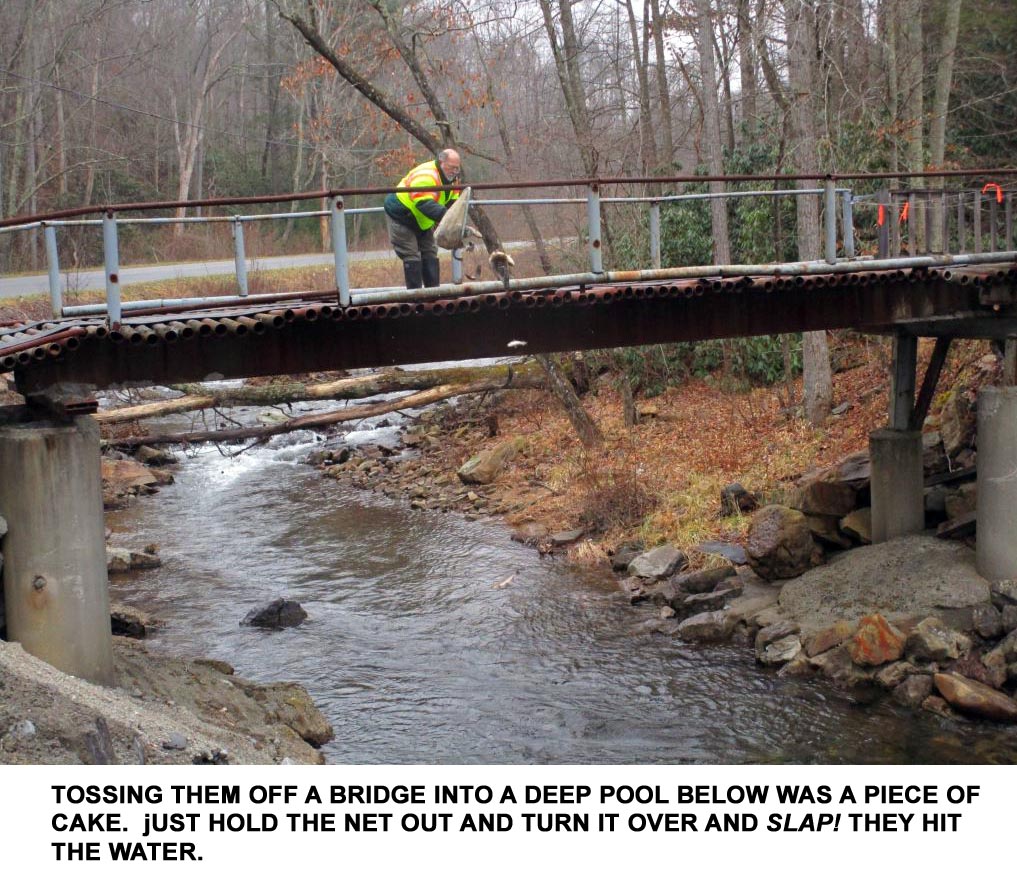

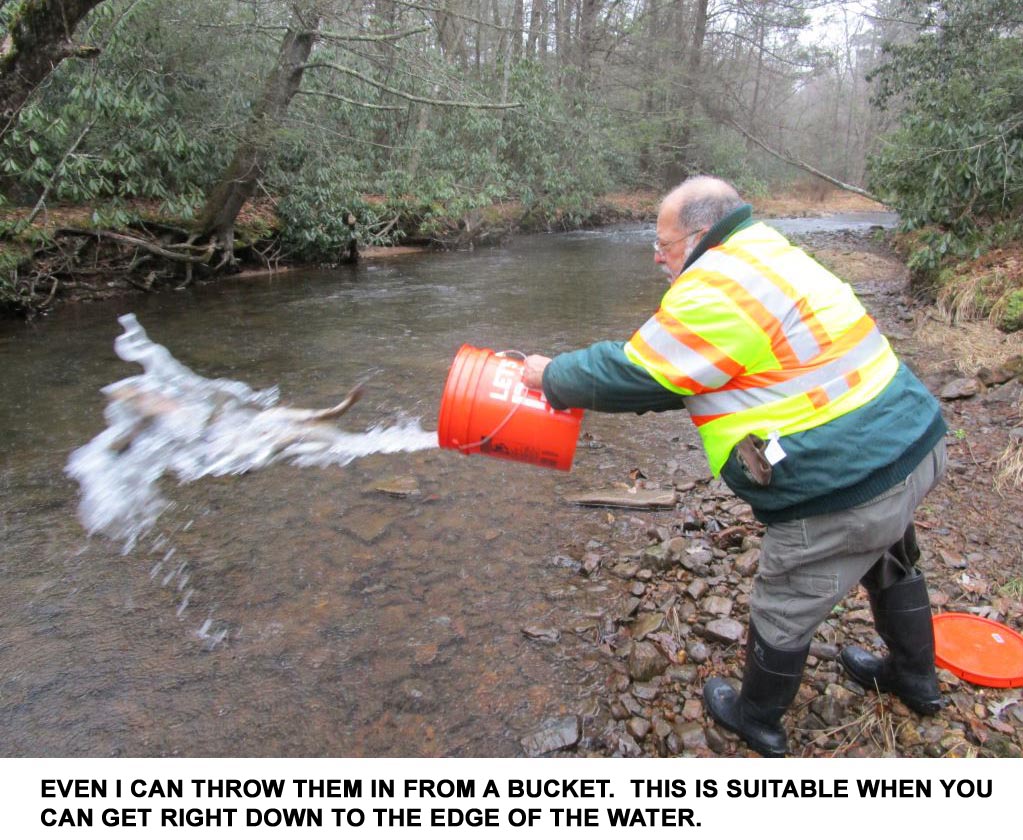

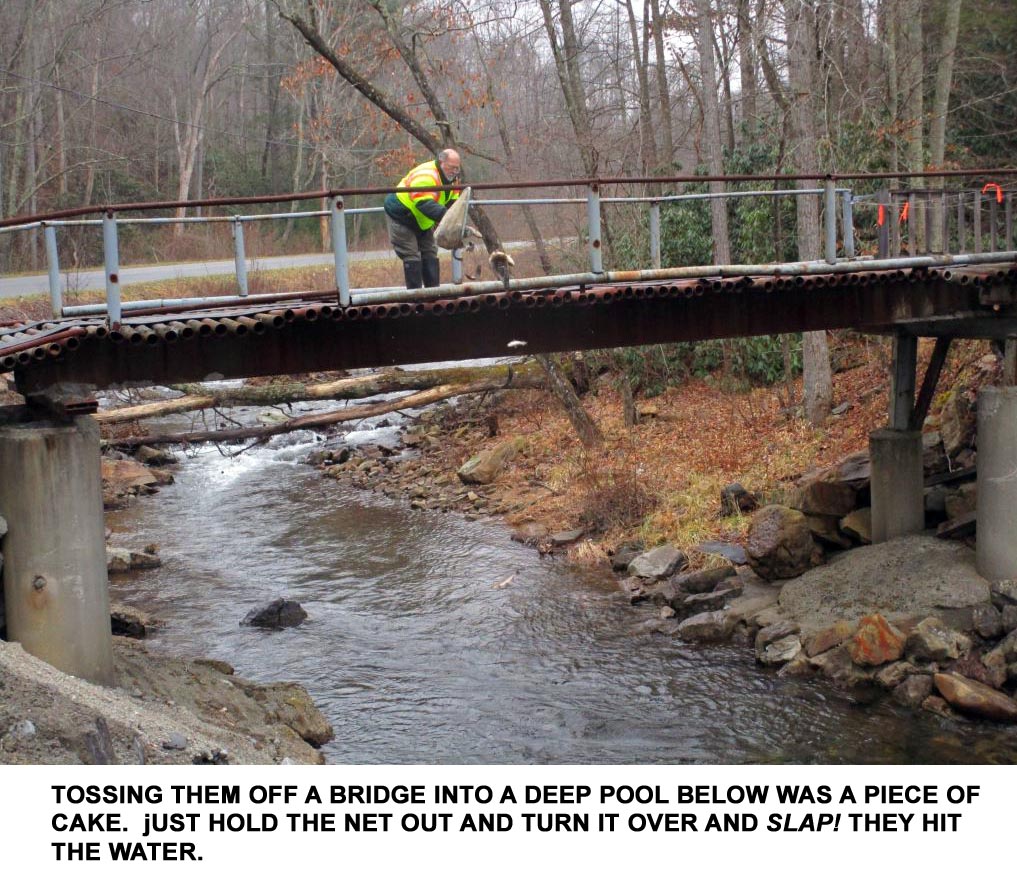

Beginning about 9:00 we commenced driving along about 7 miles of the creek, stopping to throw netfuls of fish into it. Each scoop held perhaps 20 pounds of frantic rainbow trout. Zack would stand on the truck to scoop up a netful and pass it down to one of us. We would then push through the brush to the bank of the creek and toss it into the water. Most of the places we stopped had decent size pools; in between was very fast water rushing over rocks that kept things oxygenated. Some of these fish were of very good size: 4 to 5 pounders weren't uncommon.

There's a trick to tossing fish into a creek neatly, but I have yet to learn it. The net is thrown into the air, allowing the fish to come out when the swing is stopped. The now-empty net is then withdrawn and the newly liberated fish plop into the water smartly. I couldn't manage to do this properly, it takes some practice because the net is heavy and the handles are about 10 feet long. Mostly I just turned the net over and dumped them in.

Throwing the fish so they land "hard" is supposed to "wake them up," and is alleged to be better than easing them into the water. This may be true. Regardless of how they were put in, sometimes one or two would be belly up after landing, but it did seem to be less likely with a good throw. If a fish was floating the wrong way, we'd poke it with the net handle and invariably it would right itself and then go off to hide.

Zack said the fish are fasted for three days before release. This keeps the quantity of stressed-fish poop in the truck tanks down, and also to make them easier to catch because they're hungry. Zack is a master fish-thrower. At a couple of spot where the banks are steep and high, he would stand on the truck, toss a netful into the air, and they'd hit the water 40 feet away. None of us, even the more experienced volunteers, had his level of fish-tossing ability, but Zack presumably does it every day at work, and perhaps—who knows?—he throws fish around for practice at home.

The fish are sterile polyploids, to eliminate the chances of them propagating and perhaps hybridizing with local trout. Not that it matters much if they're sterile: hardly any of them survive as much as a year even if they don't get caught. Summer water is too warm for rainbows.

The fish had to experience some considerable degree of thermal shock in the stocking procedure. The truck tank was at 55 degrees, but the creek water was a LOT colder than that: not much above freezing. There was easily a 15-degree difference as soon as they hit the water. You'd think THAT would wake them up all by itself.

To the extent a fish has a mind, I had to wonder what they thought about all this. A hatchery trout is one of the dumbest creatures on earth, and by the time they get to the size when they're ready to be released, they're between 3 and 4 years old or even a bit more. They've spent their entire lives getting three square meals a day of Purina Fish Chow, in water held at perfect temperature, with maximum oxygen, correct mineral and electrolyte balance, and zero predators. A hatchery tank must be a rainbow trout's concept of Paradise. Then, without warning, they are snatched from this watery bed of roses, shut up in a pitch-black tank on a truck (Zack assured me they get motion sickness when the truck is moving) and the next thing they know, they're flying through the air and WHAM! they hit COLD water. Do they know they've been freed? Do they know what all those big rocks are? They've eaten fish pellets all their lives, do they have any idea what a worm or a crayfish even is, let alone that they're supposed to eat it? If one remains free long enough I guess they learn these things, but they don't spend a lot of time enjoying their freedom.

The stocking dates are announced on the DGIF web site, and therefore, several cars of dedicated fishermen hoping for a trout dinner met us, and followed us as they went in. At one spot someone was already waiting for us to drop them into the creek! On the way out we saw at least one fish being pulled out of the water within 15 minutes of release. As it happens, I know the CPO who was on duty well: he's a genial guy who would smile when he wrote his mother up for a violation, which he'd certainly do. He is also about 6'5" and built like a linebacker, the sort of man you would not want to mess with, even if he weren't carrying a .40 caliber Glock, Mace, and a collapsible baton. He made a point of checking the licenses of people who tagged along behind the truck, of course; and he seemed to know a lot of them from...ahem...previous encounters.

I think I'm going to like this gig.

Virginia's Department of Game & Inland Fisheries is—as is probably true of nearly all such agencies—underfunded for the work it does. In my region, two Conservation Police Officers (CPOs) have responsibility for a vast area, covering at least two and possibly three counties. In addition, this part of the state is very rural and has a lot of hunting and fishing activity, so there are other non-LEO members of the agency who have lots to do to maintain the excellent outdoors opportunities those of us fortunate enough to live in the New River Valley enjoy.

Virginia's Department of Game & Inland Fisheries is—as is probably true of nearly all such agencies—underfunded for the work it does. In my region, two Conservation Police Officers (CPOs) have responsibility for a vast area, covering at least two and possibly three counties. In addition, this part of the state is very rural and has a lot of hunting and fishing activity, so there are other non-LEO members of the agency who have lots to do to maintain the excellent outdoors opportunities those of us fortunate enough to live in the New River Valley enjoy.